Penelope Fitzgerald Honoured

By Jeanne Rathbone

Jeanne Rathbone, Terence Dooley, Hermione Lee, Alan Hollinghurst, Marsha de Cordova MP , Emma Anthony, Hilaire and Cllr Rex Osborn at the unveiling of the plaque commemorating Penelope Fitzgerald

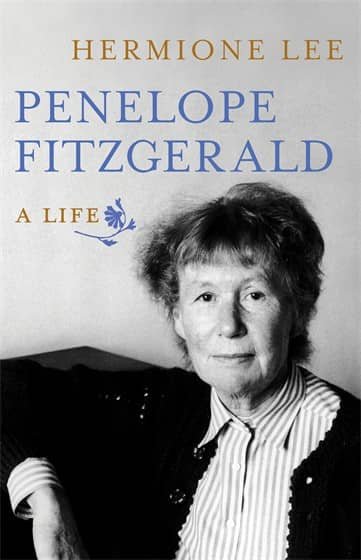

Plaque unveiled to Penelope Fitzgerald, the late-blooming, enigmatic literary phenomenon

On 2 September 2023, the author Penelope Fitzgerald was commemorated with a Battersea Society plaque on 25 Almeric Road SW11, just off Battersea Rise. This had been her home since 1975 when she and her husband Desmond came to live with her eldest daughter Tina, husband Terence Dooley and their young family. It was at Almeric Road that she was living when she won the Booker Prize for her novel Offshore in 1979.

Marsha de Cordova, MP for Battersea, unveiled the plaque on the Saturday and we heard from Penelope’s biographer Hermione Lee, her son-in-law and literary executor Terence Dooley, co-owner of the house Kevin Hird and Wandsworth Borough Council Heritage Champion and blue badge guide, Councillor Rex Osborn. Excerpts from Offshore were read by Emma Anthony of the Wandsworth Heritage Service, Battersea Society Heritage committee member and poet Hilaire, and Booker prize winner Alan Hollinghurst.

Penelope Fitzgerald, 1916-2000, was a Booker prize-winning novelist, poet, essayist and biographer. In 2008, The Times included her in their list of ‘50 greatest British writers since 1945.’ In 2012, The Observer named her final novel, The Blue Flower, one of the ‘10 best historical novels.’ What was exceptional about her is that she didn’t start writing until she was around 60. She tended to comport herself, as Julian Barnes wrote, ‘like some harmless, jam-making grandmother who scarcely knew her way in the world.’

Young Penelope Knox

The noted late starter from a remarkable family

Penelope launched her literary career in 1975, at the age of 58, when she published a biography of the artist Burne-Jones. As Alan Hollinghurst in his review wrote, ‘The promised start was deferred by nearly forty years’ She was, as she said, ‘an old writer who had never been a young one.’

That biography was followed two years later by The Knox Brothers, a biography of her father and uncles. She came from a fascinating family. It is as if she had to write about them, to get some things written and out of the way, before embarking on her nine novels.

Her father Evoe and his three brothers Dillwyn, Wilfred and Ronald Knox were the subject of her second book. Dillwyn was a mathematical genius, a classicist and Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge, who became a cryptographer and whose work at Bletchley Park during WW11 was instrumental in cracking the Enigma code. He was fiercely agnostic. Wilfred, shy and awkward, eventually joined a celibate religious order, and wrote a book, Meditation and Mental Prayer, treasured by his niece. Ronald, who learned Latin and Greek at age four, and was remembered as ‘the cleverest boy in Eton’s living memory,’ became famous as his generation’s most prominent Anglican convert to Catholicism. He wrote detective stories, made a new translation of the Bible, and became the Catholic chaplain of Oxford University. Her father said of himself that the church did not seem to ‘rub off properly’ on him. He left Oxford without a degree, going on to a successful career as a satirical journalist, first as a columnist for the magazine Punch and later as its editor.

Penelope’s father Edmund Valpy Knox, known as Evoe, was son of the Bishop of Manchester. Her mother Christina Hicks, daughter of the Bishop of Lincoln, had been one of the very first women to study at Somerville College, Oxford. Her daughter proudly followed in her footsteps. Penelope, their second child, was born in December 1916 in the Old Palace of the Bishop of Lincoln. Both parents came from ecclesiastical low-church families: high-minded, industrious, ambitious, doers of good works. At this time the Old Palace had been ‘thrown open to a pitiful group of Belgian refugees’ and later became a Red Cross hospital. Evoe was about to leave for the trenches and would be sent home wounded from Passchendaele.

During World War II, Penelope’s brother Rawle spent three and a half years as a prisoner of war in a Japanese camp. Just before his return, he sent a letter to his father saying that if ever he wanted to ask him about what had happened in the camp, Rawle would tell him. He came back, and no one in the family ever asked him anything.

Early years

When Penelope was five, the family moved to Hampstead, which she described as ‘a place of high thinking, plain living and small economies ... ham-and-beef shops, old bookstalls and an amazing number of cleaners and repairers.’

When she was eight, Penelope was sent away to Deerhaddon School in Eastbourne, which she hated, then at 13 to Wycombe Abbey on a scholarship. ‘The stories I wrote at the age of eight and nine did not bring me the success I hoped for,’ she noted wryly in an essay of 1980.

Her triumphant ascent in 1935 to Somerville, Oxford, like generations of her family before her, was shadowed by the death of her mother that spring from cancer. Her mother was described as ‘a gentle, spirited, scholarly, hazel-eyed girl, a lover of poetry and music, a determined, though not a militant, suffragette.’ She also sometimes wrote for The Manchester Guardian, so Penelope grew up, she said, ‘dipped in ink.’ The loss that haunts Fitzgerald’s fiction, even the funniest, originated from this first irreplaceable loss of her mother.

But she worked hard and played hard. She was in a set known as ‘Les Girls’ and acclaimed as a blonde bombshell. She studied with J. R. R. Tolkien. Alan Hollinghurst wrote of her, “Just before Penelope Knox went down from Oxford with a congratulatory First in 1938, she was named a ‘Woman of the Year’ in Isis, the student paper. She wrote a few paragraphs about her university career, dwelling solely on what had gone wrong. She’d come to Oxford expecting poets and orgies, and had seen few of the one and none of the other…..’I have been reading steadily for seventeen years; when I go down I want to start writing.’” Her nickname, which she kept for life, was Mops.

Wedding of Desmond and Penelope

Wartime marriage

In summer 1940 she fell in love with Desmond Fitzgerald, an Irish soldier whom she met at a wartime party, a ‘dashing ... tall, dark and handsome’ trainee barrister and lieutenant in the Irish Guards. In his 2014 review of the biography of Fitzgerald by Hermione Lee, A. N. Wilson wrote: ‘…at Somerville with a clever pre-war generation… she met Desmond Fitzgerald, a brave young soldier, and married him. The reader, but not the author, of this biography, wonders whether his gallantry as an officer with the 1st Battalion, Irish Guards, in North Africa and Italy, led to his later problems – his alcoholism and his inability to do much with his life….’

The couple married in 1942. After Desmond’s war service, for which he was awarded the Military Cross, the couple settled in Hampstead. Their first child, a boy called Valpy, was born in 1947 and the year after they moved into a cottage in Hampstead, ‘an appealing couple in their early thirties’ living in a ‘shabby-smart bohemian environment which suited them – or suited Penelope – very well.’

Two daughters arrived: Tina (born 1950) and Maria (1953) and were dressed in ‘Victorian-style clothes’ with ‘proper party dresses and sashes.’ There were drinks and dinner parties, an au pair and a charlady, a big car, a black taffeta dress with a yellow turban. ‘They were living a comfortable middle-class life: in fact, they were living beyond their means.’

She and Desmond co-edited a magazine called World Review, in which J. D. Salinger’s ‘For Esmé with Love and Squalor’ was first published in the UK, as were writings of Bernard Malamud, Norman Mailer and Alberto Moravia. Penelope also contributed, writing about literature, music and sculpture.

Towards the end of 1952, when Penelope was pregnant with Maria, she left the infant Tina behind and sailed with Valpy to New York on the Queen Mary. From the US they travelled by Greyhound bus to Mexico, to visit the Delaneys, two old ladies of Irish extraction, a sister and sister in law, because ‘it was hoped that ... they might take kindly to my son and leave him all their money.’ But the plan failed, and mother and son ‘left on the long-distance bus without a legacy, but knowing what it was to be hated.’

In 1957, ‘quite suddenly’, the Fitzgeralds did a flit from Hampstead for a former oyster warehouse in Southwold, the basis for the fictional damp bookshop and the beginning, perhaps, of the fascination with dampness. There were terrible rows, huge bills were run up and never paid, and Valpy had to leave Westminster after two terms. Desmond worked in London during the week. They left Southwold after selling all their furniture on the street. This of course inspired her novel The Bookshop which was shortlisted for the Booker prize and also made into a film.

From Southwold to Thames houseboat disaster

In 1960 they moved back to London, into Grace, ‘an old wooden barge which for many years had carried cargoes up and down the east coast under sail, but was now a battered, patched, caulked, tar-blackened hulk.’ Grace was moored on Chelsea Reach, then as now ‘one of the very grandest parts of London.’ The boat was cold, leaky, rat-infested and insanitary, ‘a total disaster area ... mortifying and chaotic.’ There was no stove, no way to do laundry. At low tide it canted on stinking mud flats. The family was told to emit wastewater — and to use the toilet — only while the tide was going out.

In December 1962 Desmond was disbarred for ‘forging signatures on cheques that he cashed at the pub.’ The end of his legal career led to a life of poverty for the Fitzgeralds;

six months later Grace sank and was towed away, destroying pretty well all the Fitzgerald family papers. The girls, luckily, were out; the cat was clinging to the mast; Desmond was nowhere to be seen. Penelope, after losing the houseboat she had been living on for three years, arrived at Westminster Tutors where she was teaching and announced to her students, ‘I’m sorry I’m late, but my house sank.’ Too proud to ask her father for help, Fitzgerald took her children into restaurants to eat the free bread and olive oil before pretending to dislike the menu and going somewhere else where the charade would be repeated.

Homeless, they lived for four months in a homeless centre. Towards the end of 1964 Penelope was going through Desmond’s pockets when she found a letter, dated six weeks previously, offering the family a council flat. They moved to 185 Poynders Gardens, a three-bed flat on a classic brick-built London County Council estate. Penelope continued sleeping alone, in the living room. She called it ‘Squalid Council Estate’ in her letters, but it seemed fine to friends who visited. She and Desmond went on living there until his final illness in 1975 when they went to live with Tina and her husband Terence Dooley at 25 Almeric Road, occupying the downstairs. Terence described them as ‘two kind, intelligent and funny people who simply couldn't manage the world.’

Life as a teacher

To provide for her family during the 1960s Penelope taught at the Italia Conti Academy, a drama school, and at Queens Gate School where her pupils included Camilla Shand now Queen Camilla. She also taught at Westminster Tutors, a posh crammer where her pupils included Anna Wintour, Edward St Aubyn, Tilda Swinton and Helena Bonham Carter. Penelope did not at all want to be a teacher: ‘I’d get tired of pretending to mind whether they’d done their essays or not,’ she said to her daughter Tina, but she did it for a long time, at Queen’s Gate until 1977 and Westminster Tutors until 1987 when she was seventy.

Meanwhile, she pieced together an impressive education for her own girls, with schooling at the London Oratory and Godolphin and Latymer (which was free at that time), and the price-of-a-bus-fare cultural life that was and is London’s glory: libraries and galleries and cheap tickets to the theatre (sneaking in their own pies and wine).

Package holidays and home life

As an employee of Lunn Poly, then later Thomson’s and Thomas Cook, Desmond got cheap travel as a perk, and the Fitzgeralds became great takers of package holidays, visiting the Alps in 1965 then Elba, Florence, Turkey, Madrid. The trips were done ‘on a shoestring,’ the girls once more eating the free bread and olive oil in one restaurant before ‘throwing down the menu’ and moving on to the next.

At home, Desmond did the weekly launderette run and all the ironing, while Penelope made dresses, cooked and painted her own Christmas cards. She read and studied, and Desmond helped her, driving her around to research.

As the eldest and as a boy, Valpy perhaps felt the Knox pressure to succeed more than his sisters did, not to mention the overweening love of a mother whose husband was a disappointment. Being Knoxes, they were all expected to go to Oxford – ‘it would not have occurred to them not to’ – but when Valpy won a place at Trinity to read Chemistry, all he remembers of his mother’s response was disapproval that it wasn’t Balliol. A few years later, Tina went to Somerville to read Spanish, and Maria to read Physiological Sciences at Lady Margaret Hall.

Literary legacy

Penelope had worked for the BBC during the war and began writing in the 1960s. Her early fiction drew on her own life and working experiences. In 1977 she published her first novel, The Golden Child, a comic murder mystery with a museum setting inspired by the Tutankhamun mania earlier in the 1970s. The novel was written to amuse Desmond who was terminally ill and died in 1976 aged 59. The Bookshop followed in 1978. Their time spent living on the barge at Battersea Reach Cheyne Walk inspired Offshore (1979); Human Voices (1980) reflected her BBC experience; teaching at the Italia Conti stage school in London gave her the material for At Freddie’s (1982).

She said after At Freddie's that she ‘had finished writing about the things in my own life, which I wanted to write about.’ She then wrote a biography of the poet Charlotte Mew before she began a series of novels with a variety of historical settings and places. The first was Innocence (1986), a romance between the daughter of an impoverished aristocrat and a doctor from a southern Communist family set in 1950s Florence, Italy. (The Italian Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci appears as a minor character).

The Beginning of Spring (1988) takes place in Moscow in 1913. It examines the world just before the Russian Revolution through the family and work troubles of a British businessman born and raised in Russia. The Gate of Angels (1990), about a young Cambridge physicist who falls in love with a nursing trainee after a bicycle accident, is set in 1912, when physics was about to enter its own revolutionary period.

Then, in the early 1990s, she settled down for ‘about three years’, to read everything she could by and about Friedrich von Hardenberg (1772-1801), the Saxon nobleman and salt-mine manager who, three years before his death at 29, began publishing under the name Novalis, and whose hallucinatory Heinrich von Ofterdingen was chosen by Borges to be read to him on his deathbed. This became the subject of her final novel, The Blue Flower (1995), which centres on Novalis and his love for what is portrayed as an ordinary child and introduced the idea of the blue flower as the emblem of the impossible and irresistible search. Other historical figures such as the poet Goethe and the philosopher Karl Von Schlegel, feature in the story. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award 1997 and has been called her masterpiece. In 1999 it was adapted and dramatised for BBC Radio by Peter Wolf.

A collection of her short stories, The Means of Escape, and a volume of her essays, reviews and commentaries, A House of Air, were published posthumously.

‘On the whole,’ Fitzgerald wrote to her American editor in 1987, ‘I think you should write biographies of those you admire and respect, and novels about human beings who you think are sadly mistaken.’

The family archive contains many of Fitzgerald's books, described by biographer Hermione Lee as the ‘battered, treasured, much-used library of a working woman, mostly paperbacks, stuffed full of notes, marks, clippings and reviews, written all over from cover to cover in Fitzgerald's clear, steady, italic handwriting. They provide the entry point to a remarkable writer's reading life.’ Also in the archive were correspondence from A.S. Byatt, Muriel Spark, A.N. Wilson, Rebecca West, Nina Bawden and Penelope Lively. These are now with the British Library.

When she won the Booker prize she was treated condescendingly by the BBC's resident bookheads because they thought another author should have won and didn’t know what to make of the 60 year old woman author.

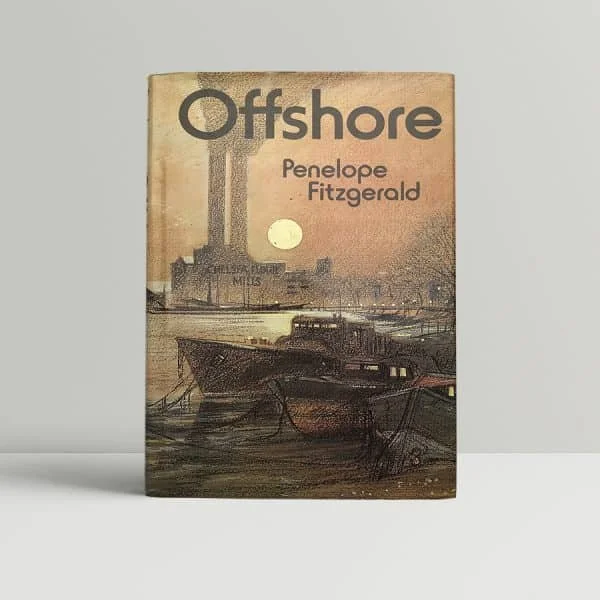

Booker prize-winning novel

Offshore

Penelope’s Booker prize-winning novel is set among the houseboat community of the Thames and the latest reprint has a new appreciative introduction from Alan Hollinghurst.

On Chelsea Reach, a mixed bag of the temporarily lost and the patently eccentric live on houseboats, rising and falling with the tide of the Thames. There is Nenna, an abandoned wife and mother of two young girls running wild on the muddy foreshore, whose domestic predicament, as it deepens, will draw this disparate community together. There is good-natured Maurice, by occupation a male prostitute, by chance a receiver of stolen goods. And Richard, an ex-navy man whose boat, much like its owner, dominates the Reach.

The two girls Tilda and Martha go mudlarking with a handcart looking for tiles in the mud in Battersea. They retrieve two tiles which Tilda recognizes are by William de Morgan. They take them to an antique dealer at a shop called Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme which nets them three precious pounds. The girls visit Old Battersea House and meet the very old woman who lived there who was Mrs Wilhelmina Stirling, keeper of the de Morgan collection. Penelope too, of course, had visited the house which has now got a Battersea Society plaque.

Penelope Fitzgerald the enigma

One of the qualities most frequently ascribed to Fitzgerald is that of 'reticence.’ Terence Dooley, in his introduction to Fitzgerald’s posthumously published letters, tells how she could convey what she wanted in letters in a way she didn’t feel able to in person: ‘She wrote to her friend giving instructions of how to get to her then home: The 49 stops at Arding and Hobbs, the Mecca of south London and get out at the next request stop, quite soon after, St John’s Road, and walk on a bit, then turn left up Battersea Rise and Almeric Road is first on the right – at the bottom is a notice board of the Tulipean Brethren, a religious sect don’t go in there – we are at 25 with a laurel hedge.’

The laurel hedge is no more as it got blight but the house bearing the plaque is lovely. The day of the unveiling, owner Kevin Hird gave the Fitzgeralds, Hermione Lee, Alan Hollinghurst and me a tour. Their daughter Maria was able to revisit the upstairs room where they held her intimate wedding party and the room with the French window where Desmond had died.

When Tina and Terence gave up teaching and left for the west country with their growing family, Fitzgerald left Almeric Road and later went to live with her daughter Maria and husband John in north London. She never wanted to live entirely alone.

Penelope Fitzgerald was what would be called a bluestocking and yet she lead the life of a woman of our own time, surviving the vicissitudes of family life and money worries with which many women can identify. I have wondered if I might have passed her on the street on her way to catch a 19 or 49 bus or a train at Clapham Junction. I would love to have met her.