The Extraordinary Diederichs Duval Family

By Jeanne Rathbone

New commemorative plaque for Diederichs Duvals: remarkable for their achievements and remarkable for the family history

Wandsworth Council have honoured the Diederichs Duval family with a commemorative plaque unveiled in June at 97 Lavender Sweep. The family were extraordinary as most of them were dedicated to the campaign for women’s suffrage. Their household must have been a fascinating place during the hectic years just before World War I of intense campaigning for votes for women. One can imagine the house with bundles of leaflets, badges, sashes and posters where meetings were held, activities planned and speeches prepared. There would also have been comings and goings to their various suffrage headquarters, and father Ernest going to his office for work. Then there were the stints when some were in prison and visits had to be arranged.

Emily and Ernest Diederichs Duval had nine children. Their first child, Ernest, was born in 1882. He was followed by Victor, born in 1885, Barbara in 1888, Norah 1891, Elsie 1893, Winifred 1895 and Gurney in 1897. Two children, Walter and Ivy, died in infancy; the eldest died in 1904, aged only 22. The family lived at 97 Lavender Sweep from 1884-1906 before moving to what is now 37 Elsynge Road SW18. The lovely family photo was taken in their small back garden in Lavender Sweep.

Emily and Ernest with Gurney, Barbara, Elsie and Norah (in front), c. 1904

The story behind the family name

Ernest was born Ernst Karl August Diederichs in Mainz, Germany near the border with France, His putative father, Eduard Ludwig Schott von Schottenstein, was a German aristocrat and Lutheran Protestant; his mother Emilie was the daughter of an Alsatian blacksmith. She was educated and at the age of 18 probably employed as governess to the great man’s children. Her brother Ernst took financial responsibility for his nephew and served as godfather to the child who was baptised as a Protestant.

Ernst was fostered out to a midwife and her husband, both Catholics. They died when he was 17 and so he came to Battersea, without a word of English, under the assumed surname Duval, lodging at 52 Wycliffe Road, off Lavender Hill. Ernest’s landlady was in fact his mother Emilie Diederichs. As well as landlady, she was established as a respectable unmarried teacher of French and music in a secondary school for girls. Sadly, she felt compelled to maintain the denial of her true relationship to Ernest for the rest of her life. Ernest's Home Office naturalisation file explains the origins of his fictitious name.

In the census of 1881, Ernest was a “corresponding clerk.” The role of a corresponding clerk was to deal with customers, by mail, in languages other than English; Ernest spoke both German and French. One Emily Hayes (1861 -1924) was living down the street from Ernest at 37 Wycliffe Road. Emily may have been a worker in a garment factory as her occupation was listed as machinist. Her father was a coachman, privately employed. Her mother was Battersea-born and it was in Battersea that Emily was baptised. Her grandfather owned a beer house, The Queens Arms, in what was then 1 New Road, right by Clapham Junction. The road had thirty houses which got gobbled up by the expansion of the railway and the station; it was renamed Prested Road which only had the Windsor Castle pub on that corner, since renamed The Junction.

Emily and Ernest were married in 1881 at St. Mary’s Church by the river. He was 23 and she was 20. He married Emily under his assumed name Duval, and they lived briefly under his mother's roof. Ernest’s and Emily’s first child was born the next year, at their first home, 7 Eccles Road, Battersea. Ernest risked exposing his mother by naming the boy Ernest Edward Diederichs Duval. The records show that when members of the family were naturalised in 1904, all of the children under the age of 18 had been named Diederichs Duval.

Around the time of the oldest child’s birth, Emilie Diederichs quit her teaching job and returned to the bosom of the Diederichs family in France, away from any scandal that might ensue. Ernest never saw his mother again.

Their granddaughter Jenny Slaughter wrote: “The last knowledge that I have of Emilie is a letter, written by Ernest in July 1915, to Mademoiselle Diederichs at Bourgoin, where her nephews controlled the Diederichs factories (which continued in business till 1992). The letter reads, “As you are the only person who can, for the moment, say in what town in Alsace I was registered at birth as a Frenchman, I shall be glad if you will forward the necessary information.” Ernest’s letter, unanswered, was stamped “Décédé” (deceased) and forwarded (as Ernest had requested, if undeliverable) to his son Victor.

The letter contains the telling words “Since our correspondence has ceased…” implying a rift between mother and son and speaks also of Ernest’s unhappiness at being shut out of the Diederichs family: “I have never intruded on any of them in my life, that is I have silently borne insult and contumely alone. I met one of your brothers at my house. I did not disclose my identity… In deference to you, I refrained and everything was kept in wicked secrecy.” It’s quite a heartbreaking letter, because it is evident that Emilie had loved Ernest enough to raise him herself and educate him properly, at a time when an unmarried mother was a social pariah, yet the apparent price of a comfortable retirement in France was continued denial and secrecy. Ernest seems to be at pains in the letter to underline the fact that his heirs were marrying into “society”, thus asserting that they were quite worthy to associate with the Diederichs of Bourgoin-Jallieu.

I discovered the background to the family after I had posted a blog on my website about this amazing family who lived on Lavender Sweep, which is where I have lived since 1968. My blog initially was titled the Duval Suffrage Family. Then I was contacted by Norah’s grandson Adrian Benstead from Australia who explained that Duval is only half the story. It was also Adrian who pointed out that when Ernest arrived, the Beaufoy vinegar factory was on Wycliffe Road – so everyone knew any time of the day which way the wind was blowing.

Emily the Suffragette

It was only husband Ernest that was recorded on the electoral register, of course, when the family moved around the corner from Eccles Road to 97 Lavender Sweep in 1884. Emily joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1906 but left it for the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) and became Chair of the Battersea Branch. The WFL was established in 1907 by a breakaway group, led by Charlotte Despard and Teresa Billington-Greig, who objected to the autocratic ways of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst .

The WFL was a socialist, militant organisation which agitated for women's voting rights, as did the WSPU. However while the WSPU was run like an army; the WFL was a democratic organisation and used direct action such as passive resistance to taxation and non-cooperation with the census, rather than attacks on people and property. It envisioned emancipation for women beyond merely gaining the vote. It recognised the wide-reaching disadvantages of a patriarchal society, particularly for working class women, and as such sought sweeping societal reform. Charlotte Despard was living in Battersea and well known as a socialist and campaigner then. She became the national President of the WFL and edited its magazine The Vote.

In October 1908 Emily and her seventeen year old daughter Barbara were arrested when Muriel Matters chained herself to the grille in the House of Commons. Emily paid her fine and Barbara was released after promising to refrain from further militancy until she was twenty-one. Emily was accused in court of being “a lady agitator who was bringing up her daughter to be a lady agitator.” In February 1909 Emily served six weeks in Holloway, almost all in the hospital wing suffering from acute neuritus. By spring she had served a second sentence. I have wondered if it was partly loyalty to her local suffragists like Charlotte Despard and Caroline Ganley that propelled Emily into becoming the Chair of the Battersea branch of the WFL.

She rejoined the WSPU in 1911 after four years in the WFL because she thought the WFL were not militant enough; she went on to break windows at the Local Government Board and was sent to prison for two weeks. Her son Victor was sentenced to five weeks at Pentonville prison at the same time.

Four members of the Duval family went on a deputation to Parliament: Emily, Elsie, Barbara and Victor. This was after the tenth ‘Women’s Parliament’ was called to Caxton Hall, from where they left at the start of each Parliament, the WSPU marching to the House of Commons, trying to deliver a petition to the Prime Minister.

When Emily was sentenced to six months in Winston Green Prison for breaking two windows in Regent Street, she told the magistrate that she had been “brutally knocked about.” Invoking the large numbers of young women who were driven into prostitution by poverty, she addressed the court “I should like to say that I shattered the glass because I wish the government to come to their senses, and money can replace broken glass, but it cannot replace the innocence of girls who are outraged daily…. I am prepared to die for votes for women.”

Four months into her sentence Emily went on hunger strike and was force-fed over a two week period. She gave an account of being force-fed in a statement she dictated at Birmingham WSPU office. The tube was forced down her throat which was “…agonising. It seemed as though I was being suffocated. I could not breathe. It was simply horrible.” She was helped back to her cell where her throat bled and she vomited “all over the place.” She was force-fed several more times and when released on 25th June before her sentence was complete and need to go to a nursing home to convalesce.

Emily Duval was elected Battersea Councillor in 1919 along with Caroline Ganley, who became MP in 1945 and Jessie Hockley, secretary of the Battersea Railway Women’s League. Emily died in 1924. She must have been broken hearted. Tragically, three of her daughters did not live to vote. Elsa and Barbara had succumbed in the awful influenza epidemic and Winifred died of pulmonary TB, all within months of each other. I can only imagine that Emily felt she had to keep going and serve as a councillor after the long hard struggle had won women’s right to vote and stand for public office.

Amongst Emily’s papers is a letter dated 1924 from Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence who gives news of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and writes in gratitude "...I think of Lady Constance and Emily Davidson and of you and many others... whose lives have helped to make our present work possible...".

Emily’s obituary in The Vote read: “Many of us remember with an ache of the throat even to this day how many rowdy meetings we addressed in South London parks and street corners, and the personal violence with which our gospel was received, but she, as organiser, never failed, nor faltered, nor wearied in well-doing."

Emily Duval

Elsie the Suffragette daughter

Elsie Duval (1892-1919) was the most active suffragette of the Diederichs Duval daughters. Elsie joined the WSPU in 1907, aged 15. Unlike her mother, however, she did not leave the organisation to join the WFL when the Pankhursts changed the constitution, but mother and daughter did work together for three years in the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement (MPUWE, later shortened to MPU) which brother Victor Duval founded.

Elsie Duval was arrested on 23 Nov 1911 for obstructing the police. After this event, she was officially accepted by the WSPU as a militant protest volunteer. On 27 June 1912, Elsie was arrested for smashing a Clapham Post Office window. Subsequently she was remanded for one week in custody “for the state of her mind to be enquired into” and then sentenced to one month in Holloway Prison, during which time she was forcibly fed nine times before being released on 3 Aug 1912.

She was released under the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, 1913, commonly known as the “Cat and Mouse” Act which allowed for prisoners to return to prison on recovery. Elsie was the first prisoner released from Holloway under the Act and the second to be released (her future husband Hugh Franklin was the first) from any prison. They were advised to go abroad. Elsie and Hugh separately left for France to avoid the re-imprisonment that her terms of temporary release had demanded. She spent several months working under the name Eveline Dukes in Germany, Belgium and Switzerland, armed with false testimonials provided by friends.

Hugh the suffrage-supporting husband

Hugh Franklin (1889-1962) came from a prominent suffrage-supporting Jewish family. He was one of six siblings, three brothers and two sisters. Hugh, Alice, Helen and Ellis, along with their mother Caroline, turned from the Liberal Party tradition of the family and took the path set by Caroline’s sister Henrietta who had set up the Jewish League for Women’s Suffrage. He dropped out of his engineering course at Cambridge to promote the WSPU in London. When Victor Diederichs Duval founded the MPU in 1910, Hugh joined immediately. He also declared his agnosticism and rejection of the Jewish faith.

Hugh and Elsie are the subject of a chapter in June Balshaw’s book about political partnerships and the women’s movement, “More than just a ‘sporting couple’: The Militancy of Elsie Duval and Hugh Franklin.” Balshaw wrote of the couple, “The level and extent of their commitment has not been acknowledged in subsequent histories and accounts of suffrage…Throughout the period of suffrage militancy they continued to conduct their militant activities separately, creating very distinct identities and effectively put the personal relationship ‘on hold’.”

Elsie and Hugh were finally married in a Jewish ceremony at the London Synagogue in September 1915. She had converted to Judaism. Hugh’s mother attended the wedding but not his father. Elsie had asked Emmeline Pankhurst to be one of their witnesses but she wasn’t well enough at that time. Elsie joined the Pankhursts’ Women’s Party.

Hugh joined the Labour Party in 1931 and stood unsuccessfully for MP in Hornsey and St. Albans. He was active in local politics and won a seat on Middlesex County Council and joined the Labour Party National Executive Committee.

Elsie’s and Hugh’s archive is part of the National Archive kept at the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics. Sadly Elsie died on the 1st January 1919, only 27 years old, of heart failure, a victim of the influenza epidemic. She had undoubtedly been weakened by her treatment in prison when she was force-fed.

Wedding of Hugh and Elsie

The Suffrage Movement during The Great War (WWI)

When war was declared a deal was struck by the WSPU with the Government whereby they released all suffragettes from prison and the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. While the WSPU helped recruit young men for the armed services, the pacifist WFL continued with its campaign for the vote.

Norah the Suffragette daughter

Norah (1891- 1972) the only surviving daughter of Ernest and Emily was also an active suffragette. She was arrested on 1 March 1912 along with her mother for smashing windows in Regent Street. Norah was sentenced to four months imprisonment at the Newington Sessions on 13 March 1912. She told the court, “I wish to say that what I did, I did entirely on my own responsibility, and not, as the jury would infer, as the dupe of others. I did it because I want the same political rights as my brothers enjoy today.” When asked by the judge whether she would be willing to give up breaking the law, Norah Duval replied, “No, certainly not. It is the only thing we can do. We cannot get redress in any other way.”

We also know that Norah was given shelter by the Rutter family in Leeds. Frank Rutter was an art critic and founder member of the MPU. Their home became a sanctuary for suffragettes to recuperate from hunger striking. There is an amusing account of escape in plain sight when a baker delivery van drew up outside their home. Norah was disguised as a delivery boy, while The driver, dressed as a man, was Leonora Cohen, a well-known trade unionist and one of the first female magistrates. She acted as bodyguard for Emmeline Pankhurst and was known as the “Tower Suffragette” after smashing a display case in the Tower of London. Norah was disguised as the delivery boy. She walked in to the house and in her place, similarly disguised, out walked the suffragette Lilian Lenton to be driven off. Lilian continued to evade recapture by dressing as a boy or as an old woman and became known as the “tiny, wily, elusive Pimpernel”. Rather sadly, in a BBC documentary she recounted, “Personally, I didn’t vote for a very long time because I hadn’t either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30,” reminding us that women’s suffrage was won only slowly and in stages.

Victor the Suffrage-supporting son and brother

Victor Duval (1885-1945) had been the secretary of the Clapham League of the Young Liberals. He resigned from it after seeing a woman thrown out of one of John Burn’s meetings. Burns, the one-time socialist of Battersea was very much seen as a renegade once he joined the Liberal Government; he was especially seen as such by our suffragette Charlotte Despard.

In 1909 Victor helped Marion Dunlop to stencil her petition on the walls of St Stephen’s Hall in the House of Commons. In October 1910 he co-founded the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement at a meeting held at the Eustace Miles Restaurant, on the Strand. It was based at number 13 Buckingham Street, which was also the offices of his family firm, Duval & Co. Number 18 on the other side of the road was the first offices of the WFL, to which his mother belonged, so she would doubtless have been a regular visitor to both buildings.

Victor was imprisoned for a week for a disturbance after he addressed Lloyd George outside City Temple and published a pamphlet, “Why I went to prison.” He served on the committee of the International Women’s Franchise Clubs and spent two years of World War I in Salonika serving with the Royal Engineers. He rejoined the Liberal Party and stood unsuccessfully at three elections, eventually changing his mind about socialism and joining the Labour Party. He was married to suffragette Una Dugdale in 1912.

Headlines for the bride who would not promise to obey

Una Dugdale (1879-1975) was the debutante daughter of Commander Edward Stratford Dugdale and his wife Harriet Portman Dugdale, who were also supporters of the suffrage movement. She was a marriage reformer as well as suffragette, educated at Cheltenham Ladies College, and later in Hanover and Paris where she studied singing. She was niece to Arthur Peel, 1st Viscount Peel, Speaker of the House of Commons.

In 1907, after hearing Christabel Pankhurst speak in Hyde Park, Una joined the WSPU. She worked alongside Emmeline Pankhurst campaigning for women’s rights and the vote in tours across Scotland. In 1909 she was arrested and imprisoned for a month following her involvement in the raid on the House of Commons. Una was the co-founder and treasurer of the Suffragette Fellowships.

Her sisters Daisy and Joan were also active suffragettes. Joan wrote a play, “10 Clowning Street” about an anti-suffragist Prime Minister who sends his three daughters out into the “real world” to get jobs, convinced that all suffrage campaigners are just single women needing distraction through work to stop them agitating for the vote. Instead, his daughters become radicalised.

Una met Victor when he acted as best man at Frank Rutter’s wedding. They married on 13 January, 1912 at the Savoy Chapel. She saw marriage as an equal partnership. Her father accompanied her down the aisle but did not “give her” to her future husband. Famously, she scandalised society by refusing to include the word “obey” in her vows, as trumpeted in a headline in The Mirror. She was advised that if she did not promise to obey, the marriage would not be legal, but still refused. The officiating clergyman said that he hoped an amended form of the service would be created. The suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst, Constance Lytton and the Pethick-Lawrences all attended, dressed in WSPU colours.

I found newspaper references to the wedding in international newspapers including the Chicago Examiner and the New York Herald. I also discovered that Victor’s best man was the actor Ernest Thesiger who played Dr Septimus Pretorius in The Bride of Frankenstein with our own Notable Woman of Battersea, Elsa Lanchester.

There is a wonderful BBC radio recording of Una Duval: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/suffragettes/8305.shtml

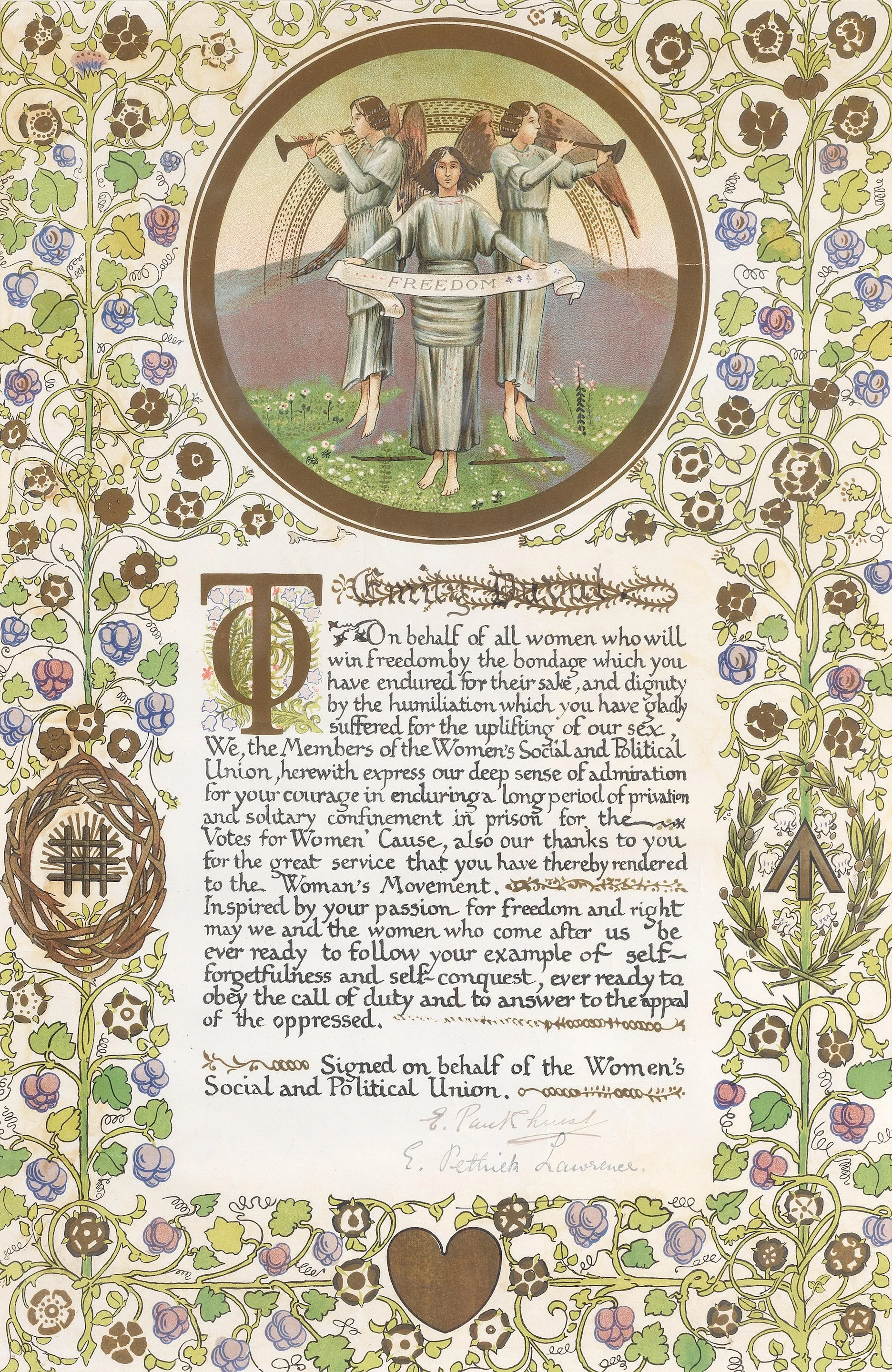

The WSPU certificate

The WSPU gave certificates to all suffragettes who were imprisoned for the cause. They were designed by Sylvia Pankhurst to incorporate the purple, green and white colours that the WPSU had adopted in June 1908. Their Angel of Freedom device was a strong “brand” logo also used on WSPU artefacts such as tea sets and medallions.

The certificates were signed by Emmeline Pankhurst. The inscription on the one given to Emily read: “On Behalf of all Women who will win freedom by the bondage which you have endured for their sake, and dignity by the humiliation which you have gladly suffered for the uplifting of our sex, We, the Members of the Women's Social and Political Union, herewith express our deep sense of admiration for your courage in enduring a long period of privation and solitary confinement in prison for the 'Votes for Women.”

WSPU Certificate awarded to Emily Duval

Diederichs Duval plaque unveiling

Opposite Clapham Junction Station in Grant Road is the building housing the Winstanley/York Road regeneration team. I was chuffed that this building has been named Duval House, a name I had suggested.

I was even more delighted when the Diederichs Duval family were selected by the Wandsworth Heritage Group (of which I am a member) for the 2023 Wandsworth Council green plaque. It was a scorching day on Friday 9th June when we had the unveiling ceremony.

It was such a delight to meet the Diederichs Duval descendants at last. I invited them to meet at our house as they gathered from their homes in London, Scotland, Yorkshire and France. I was asked by Emma Anthony from the Wandsworth Heritage Service to MC and gave a little of the background of the amazing Diederichs Duval suffragist family. Many of us wore Votes for Women sashes.

Speakers included Jenny Slaughter, granddaughter of Norah, Alesha De Freitas from the Fawcett Society, Cllr Rex Osborn, Wandsworth Council Heritage Champion and Deputy Mayor Cllr Sana Jafri. A poem, “Cat and Mouse”, by Joolz Sparkes was read by Hilaire from their joint anthology London Undercurrents. Kate Cook, the owner of the house, read a poem by her daughter Lettice called “Shattered Glass”. We were treated to a rousing rendition from the Battersea Power Station Community Choir of “March of the Women” and “Nana was a Suffragette.” The plaque was unveiled by two of the younger generation, Sam, grandson of Jenny Slaughter, and Elsie, named after her great, great, great aunt and descendent of Victor and Una.